What Do Plants Really Need to Grow? The Circular Nutrient Solution That's Replacing Traditional Fertilizers

Modern agriculture faces a critical challenge: how to feed a growing population while protecting our environment from nutrient pollution and resource depletion. The answer lies in understanding what plants truly need at the cellular level and implementing circular nutrient systems that work with nature rather than against it.

Essential Plant Nutrients: The Foundation of Growth

Plants require a precisely balanced combination of macro and micronutrients to achieve optimal growth and development. The primary macronutrients: nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), and potassium (K): form the backbone of plant metabolism, while secondary macronutrients including magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), and sulfur (S) support critical physiological functions.

Equally important are the micronutrients, often called trace minerals, which include iron (Fe), manganese (Mn), zinc (Zn), copper (Cu), boron (B), and molybdenum (Mo). Despite being required in smaller quantities, these elements are essential for enzyme activation, chlorophyll synthesis, and cellular structure. Research demonstrates that deficiencies in micronutrients like boron can cause oxidative stress and significantly impact plant development.

The key insight is that plants don't simply need these nutrients: they need them in the correct ratios, at the right time, and in forms that are readily bioavailable for uptake.

The Linear Agriculture Problem

Traditional agriculture operates on a destructive linear model: extract nutrients from finite sources, apply them to crops, harvest the produce, and lose the majority of those nutrients through the food chain. When crops are harvested and processed into food, the nutrients pass through human and animal digestive systems and are typically excreted as waste.

This linear approach creates two major problems. First, it depletes natural nutrient reserves, requiring increasingly expensive synthetic fertilizers manufactured through energy-intensive processes. Second, it generates massive nutrient pollution as excess fertilizers run off into waterways, causing algal blooms, dead zones, and groundwater contamination.

Studies show that conventional agriculture loses approximately 50-90% of applied nitrogen and up to 80% of applied phosphorus through leaching, runoff, and volatilization. This represents both an economic loss for farmers and an environmental catastrophe for aquatic ecosystems.

Circular Nutrient Systems: Closing the Loop

Circular nutrient systems represent a paradigm shift toward sustainable agriculture by capturing, recovering, and reusing nutrients to fulfill fertilizer demands while preventing environmental pollution. This approach transforms waste streams into valuable resources, creating closed-loop systems that minimize external inputs.

Water Recirculation and Hydroponics

Advanced hydroponic systems exemplify circular nutrient principles through precise water and nutrient management. In these systems, nutrient solutions are continuously recirculated rather than discharged, reducing fresh water consumption by up to 90% compared to traditional irrigation. Unused nutrients are captured, filtered, and reapplied, ensuring virtually nothing goes to waste.

The efficiency of these systems depends heavily on water quality. Contaminated municipal water containing chlorine, fluoride, and heavy metals can disrupt nutrient uptake and harm beneficial microorganisms essential for plant health. This is where proper water treatment becomes crucial for optimizing circular nutrient systems.

Designer Biochar Technology

One of the most promising innovations in circular agriculture is designer biochar: engineered charcoal-like materials created through controlled pyrolysis of organic matter. Researchers have developed specialized biochars that selectively capture dissolved phosphorus and nitrogen from agricultural runoff and sewage.

These nutrient-loaded biochars then function as slow-release fertilizers, providing sustained nutrient delivery while improving soil structure and water retention. Studies indicate that biochar application can increase crop yields by 10-42% in soil-based systems and promotes plant growth in 77% of substrate-based cultivation trials.

Integrated Treatment Systems

Advanced circular systems now combine multiple technologies into comprehensive treatment networks. Bioreactor and biochar-sorption-channel (B2) systems integrate woodchip bioreactors to remove excess nitrate nitrogen alongside designer biochars that capture phosphorus and ammonium nitrogen from agricultural drainage water.

The captured nutrients are periodically harvested and redistributed as fertilizer, maintaining nutrients within the production cycle while dramatically reducing synthetic fertilizer requirements.

The Critical Role of Water Quality

Water quality serves as the foundation for effective circular nutrient systems. Municipal tap water often contains chlorine, chloramines, fluoride, and heavy metals that interfere with nutrient uptake and can be toxic to beneficial soil microorganisms. These contaminants create barriers to optimal plant growth regardless of nutrient availability.

Research demonstrates that plants watered with properly treated water show significantly improved growth rates, enhanced nutrient uptake efficiency, and stronger resistance to environmental stress. The difference becomes apparent when comparing plants grown with untreated municipal water versus those receiving water that has been purified and re-mineralized with essential trace elements.

Proper water treatment removes harmful contaminants while preserving or adding beneficial minerals that support both plant health and soil microbiology. This creates optimal conditions for nutrient cycling and uptake within circular systems.

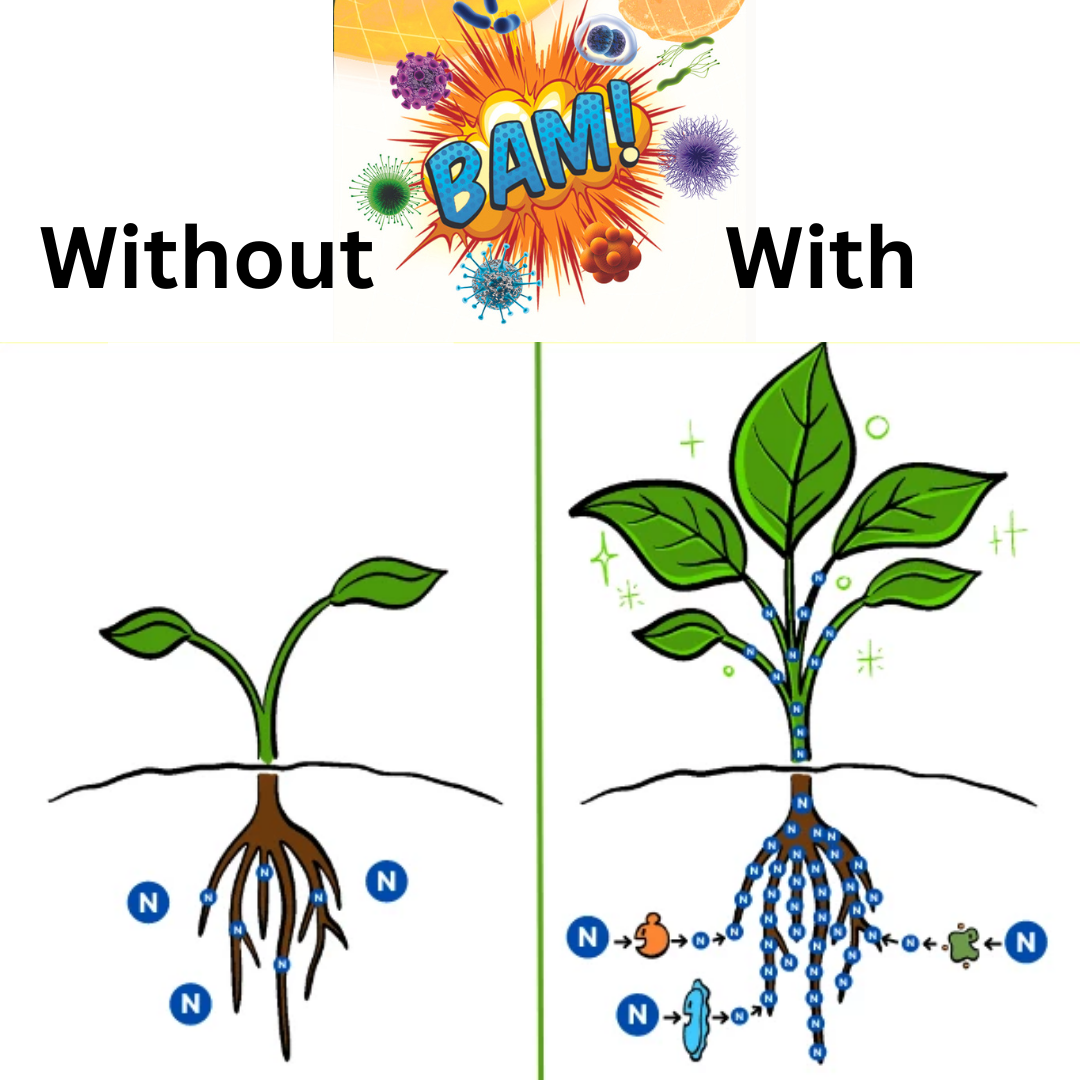

Microbial Partnerships in Nutrient Cycling

Circular nutrient systems recognize the vital role of soil microorganisms in nutrient cycling and plant health. Beneficial bacteria and mycorrhizal fungi form symbiotic relationships with plant roots, dramatically expanding the root surface area and improving nutrient absorption efficiency.

These microbial partnerships are particularly important for accessing phosphorus, which often becomes bound in soil complexes and unavailable to plants. Mycorrhizal fungi can increase phosphorus uptake by up to 300% while simultaneously improving plant resistance to drought and diseases.

However, chlorinated water and synthetic pesticides commonly used in conventional agriculture destroy these beneficial microorganisms, breaking the natural nutrient cycling mechanisms that plants have evolved to depend upon.

Economic and Environmental Benefits

The transition to circular nutrient systems offers compelling advantages across multiple dimensions:

Resource Conservation: Circular systems dramatically reduce dependence on external fertilizer inputs while conserving water resources through recirculation and reuse.

Cost Efficiency: Recovering nutrients from waste streams substantially lowers fertilizer expenses. Farmers report 30-60% reductions in fertilizer costs when implementing comprehensive circular systems.

Environmental Protection: Preventing nutrient runoff protects aquatic ecosystems from eutrophication while reducing greenhouse gas emissions associated with synthetic fertilizer production.

Yield Improvements: Optimized nutrient delivery and improved soil biology often result in higher crop yields and better crop quality compared to conventional approaches.

Implementing Circular Solutions

Successful implementation of circular nutrient systems requires attention to several key factors:

Water Treatment: Start with high-quality water free from contaminants that interfere with nutrient uptake and soil biology. Remove chlorine, fluoride, and heavy metals while ensuring adequate mineral content.

Soil Biology: Establish and maintain healthy populations of beneficial microorganisms through inoculation and avoiding practices that harm soil life.

Nutrient Monitoring: Implement precise monitoring systems to track nutrient levels and plant uptake, enabling real-time adjustments to maintain optimal ratios.

System Integration: Design systems that capture and recycle nutrients at multiple points in the production cycle, minimizing losses and maximizing efficiency.

The Future of Sustainable Agriculture

Circular nutrient systems represent more than just an alternative farming method: they embody a fundamental shift toward regenerative agriculture that works in harmony with natural cycles. As concerns about environmental sustainability and resource depletion intensify, these systems offer a pathway to maintain agricultural productivity while healing damaged ecosystems.

The success of circular systems depends on understanding that plant nutrition is not simply about adding more fertilizer, but about creating optimal conditions for nutrient availability, uptake, and cycling. This includes providing clean water, maintaining healthy soil biology, and implementing closed-loop systems that conserve resources while protecting environmental quality.

By embracing these principles, we can transform agriculture from a source of environmental degradation into a regenerative force that builds soil health, conserves water resources, and produces nutrient-dense food while supporting thriving ecosystems.